The North Atlantic Treaty Organization was formed in 1949 by the United States, Canada, and 10 Western European countries in an effort to establish a security alliance against the Soviet-led East in the wake of World War II. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, NATO’s membership increased to 30 countries through multiple rounds of enlargement, expanding the alliance’s boundaries into states once aligned with the Soviets through the Warsaw Pact.

Part of the treaty includes common defense among the member nations. Article V of NATO’s founding treaty directs member states to defend any other members that come under attack.

Maintaining NATO’s readiness for this goal requires alliance members to adequately invest in their individual defense capabilities to deter, and if need be, defeat attack. As part of membership, NATO states pledge to spend 2% of their GDP on defense.

The U.S. has always had the largest monetary and resource role in NATO, and the European members used to take their defense investments more seriously when the Cold War presented a clearer Soviet threat. But since then, the bulk of European NATO members have been complacent about security despite their wealth and capabilities. This left these states ill-prepared when Russia launched the largest European conflict since World War II by invading Ukraine.

The unequal state of defense spending and increasing U.S. challenges in other regions, such as Asia, are reviving calls for greater “burden sharing” within the alliance to reduce NATO’s dependency on the United States for its front-line defense.

Long-term, the U.S. should encourage even more fundamental “burden shifting” within NATO to improve Europe’s capability to defend itself against attack without frontline U.S. support.

Allied burden sharing during the Cold War

During the height of the Soviet threat in the Cold War, the U.S. had over 400,000 troops deployed to Europe, specifically in West Germany, to respond in the event that a conventional war broke out between Soviet members and the West. In coordination, European allies generally also maintained larger defense budgets as a percentage of their GDP, and sizeable standing armies.

Joint NATO training during the Cold War. These were coordinated efforts by NATO members to counter the Soviet Union.

West Germany, for example, had nearly 500,000 active troops in the Bundeswehr, its military, for most of its Cold War existence, and could call up 1.3 million reservists.

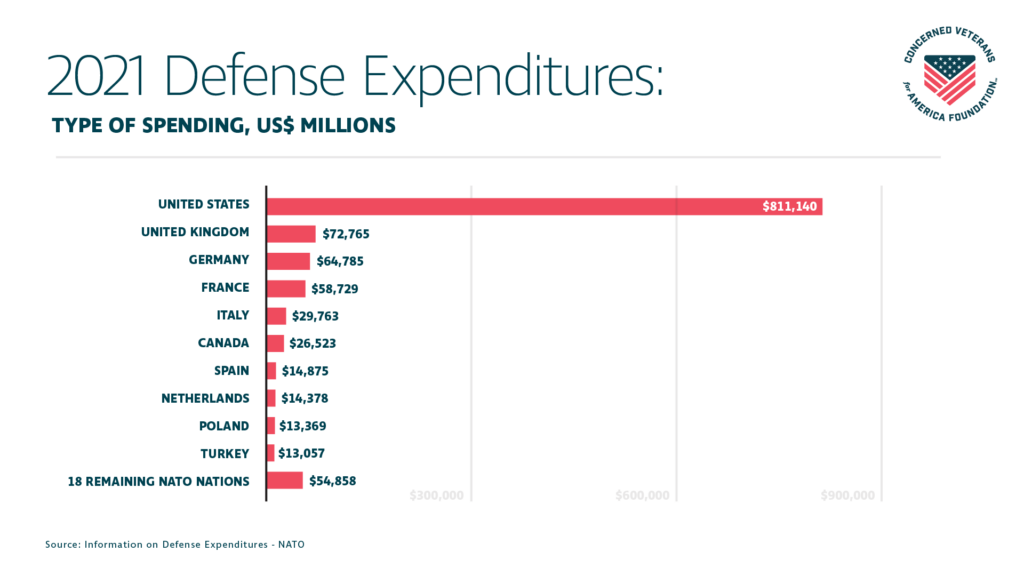

But when the Cold War ended, this cooperation and burden sharing changed. European armies shrank by hundreds of thousands of troops, and their defense spending dramatically decreased. Conversely, the American defense budget has grown dramatically. While the 1990s saw a time of defense cuts, American defense spending in that period made up 59% of NATO defense spending. This percentage was up to 70% by 2015.

Europe doesn’t invest nearly enough in NATO’s security

In 2006, recognizing the growing issues with unequal defense investments within the alliance, NATO member states agreed to set a target of spending a minimum 2% of GDP on defense spending to maintain readiness. In 2014, they recommitted themselves through a more formal pledge at NATO’s summit in Wales. However, fewer than half of the member states meet this goal every year. As of 2022, only nine members are meeting the target.

Given our immense, globally-focused defense budgets, the United States has always met and far exceeded the 2% minimum, reaching 3.47% of real GDP in 2022. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for other major NATO members with large economies. Additionally, several of the small member states are meeting the target, but their defense spending doesn’t amount to much in the grand scheme.

The three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, for example, each spend over 2% of GDP on defense. This is understandable considering these countries, bordering Russia, are NATO’s most vulnerable to potential attack.

But while they are meeting the NATO defense spending target, their GDPs are significantly smaller than those of larger NATO states. These countries are making a commendable defense effort with the resources they have, however their absolute contributions to the alliance are minor. The Baltic states’ membership in NATO presents a strategic liability for NATO’s deterrent credibility as a whole given that their small, Russia-adjacent territory is hard to defend.

Conversely, large states such as Germany, which has the largest economy in NATO after the U.S., only spent 1.44% of its GDP on defense in 2022. Germany’s track-record of underinvestment in its military since the end of the Cold War has left its military in a state of considerable unreadiness despite the country’s significant economic resources and technological capabilities.

Germany should be a leader in efforts to develop Europe’s defensive capabilities and coordination to reduce dependence on the United States. Unfortunately, Germany faces, as one defense scholar put it, “decades of underinvestment and political neglect of the armed forces”.

In 2018, German Parliamentary Armed Forces Commissioner Hans-Peter Bartels reported that the Bundeswehr was unprepared and underfunded. Bartels reported that there were over 20,000 vacant officer positions and that none of the country’s submarines or large transport planes were usable at the end of 2017 due to needed repairs and lack of spare parts. Furthermore, many pilots were unable to train because too many aircraft were out of commission at once.

By Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, things had not turned around. The chief of the German army a month later said that the Bundeswehr “is more or less broke. The options we can offer policymakers to support the alliance are extremely limited.”

Initially, Germany looked to be reversing its previous course. It set up a €100 billion modernization fund to improve its defenses, seen internationally as a major turning point. Nevertheless, this gesture has floundered.

Germany recently backtracked on this plan and revealed it would not be meeting the 2% defense spending target for at least the next few years, furthering the reliance on the U.S. and other nations that are spending the pledged amount on their defense.

Even NATO militaries meeting 2% defense spending targets face obstacles that limit their ability to assist the alliance with operations elsewhere in Europe.

The UK, for its part, has historically been more committed to its defense spending than many Western European states. Britain reached 2.12% of GDP on defense spending in 2022, but in June it was reported the UK was reducing the size of its military and would not be capable of deploying an armored division to the European continent until 2030 at least. This is a far cry from one of Britain’s crowning peacetime Cold War logistical achievements—rapidly deploying over 50,000 troops from the UK to West Germany as part of Exercise Lionheart in 1984.

Sadly, Britain has even delayed a recently planned spending increase that was meant to put the UK on track to achieve defense spending at 3% of GDP by 2030, a target now seriously in doubt.

Similarly, Greece spends a higher percentage of its GDP on defense than the U.S. and maintains the second largest force of tanks of all European NATO countries, second only to Turkey. But this Greek force is not outfitted for alliance support elsewhere in Europe. Rather, its defenses are a hedge against historic rival and fellow NATO member Turkey, with whom relations have been rapidly deteriorating.

Defense coordination can help Europe get more bang for its buck

Russia’s aggression should move more European countries to end their security complacency. Despite the lackluster showing of so many NATO-Europe members, some smaller nations, such as Belgium, the Netherlands, and Romania announced goals to meet 2% spending targets.

But whether or not any NATO-Europe countries actually end up following through on meeting these targets, they also need to make sure that they are getting the most out of their spending to begin with through greater coordination.

At the start of the war in Ukraine, the European Commission, one of the governing bodies of the European Union, issued a report outlining major capability gaps that European militaries face and routinely rely on the U.S. to fill. Examples include mid-air refueling tankers, modern fighter aircraft, and missile systems for air and sea defense.

European institutions such as the EU’s European Defence Agency exist to help European countries work together to close these gaps. Ideally through coordination, European countries can pool their resources to save money on developing expensive weapons systems. In other areas, these institutions can help reduce unnecessarily repetitive spending by helping different countries build capability specializations. This way, smaller European countries can work together to collectively develop the capabilities they more routinely rely on the U.S. to provide.

But Europe must do far more. Despite limited efforts to promote greater cooperation, European defense coordination in practice remains shockingly rare for a continent with a major war underway.

How can the U.S. encourage Europe to take its security seriously?

The best way for the U.S. to promote greater European burden sharing is to stop encouraging Europe to do less through U.S. policy.

For example, 100,000 U.S. troops are not needed to prevent Russia from conquering NATO territory. Moscow will be rebuilding its forces for decades, regardless of how its war in Ukraine ends, and it is in no condition to launch successful invasions of NATO territory in the near-term. Compared to the Cold War, the conventional balance of power has never been more favorable to NATO-Europe.

By shifting its role in NATO from front-line defense to logistical support, the U.S. can demonstrate that while it is committed to the Alliance, it does not intend to do the bulk of the heavy lifting that Europe is capable of taking on itself.

In the short-term, U.S. policymakers can also improve transparency about burden sharing imbalances by requiring more reporting on what allies are spending in comparison to the U.S. and pledged amounts. This transparency has gained traction in the last few Congresses with lawmakers introducing bills to establish reporting for oversight.

Why is rebalanced burden sharing in the U.S.-NATO alliance important?

Rebalanced burden sharing is important because potential conflicts affect countries differently.

The status quo of the U.S. essentially subsidizing European defenses is not sustainable, and America has a strong national interest in a Europe that can take the lead in its own defense without requiring American intervention.

Europe has the wealth and technological capability to defend itself—particularly against a weakened Russia—if it commits to do so. And the U.S. has bigger challenges in regions such as East Asia, where China is a far more powerful potential adversary.

Though U.S. influence over European strategy may be reduced if American troops aren’t bearing the brunt of Europe’s security burdens, a less overstretched America will be more secure and better able to respond to individual threats to its core interests.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is of far more importance to European security than the United States’ own, but nevertheless the U.S. has pledged substantial billions more in aid to Ukraine than its European NATO allies.

America’s European allies should be more concerned than Washington about a war that affects their security more. And despite its rightful sympathies for the Ukrainian cause, America should not be outspending the rest of the world combined on aid in a conflict that doesn’t significantly affect American security, and is at best secondary to U.S. challenges in Asia.

How should the U.S. approach alliances with other nations? Read more.