U.S. alliances, especially those with Europe, have evolved since our Founders first warned of their potential to tie America’s fortunes to those of other nations. While America’s position in the world has changed dramatically since then, handling our alliances and partnerships with appropriate caution to ensure they truly benefit American interests remains crucial.

Historically, under the right circumstances, alliances have often been prudent for protecting vital U.S. interests. Today, the heightened risk of conflict with nuclear-armed Russia requires us to approach our alliance relationships correctly so that we don’t unduly limit our ability to manage our relationships with our competitors and adversaries.

Benefits and drawbacks in alliances

At a general level, America is wise to maintain friendly relations with its European allies and partners. With many of these nations we share similar liberal democratic values, close economic and cultural ties, and a commitment to engage in robust security cooperation. Nevertheless, the extent of the U.S.’s formal security commitments abroad should always be a subject of discussion.

To be sure, alliances such as NATO have brought many clear positives. For instance, the U.S. and Europe have benefitted from the combined command structure that NATO built up, which enables them to more effectively coordinate forces against a potential Russian attack, as well as regular military exercises honing these capabilities.

In an ideal world, a structure such as NATO’s would also help less wealthy countries maximize the efficiency of their defense spending by pursuing individual specialization that benefits the broader alliance and pooling resources to cooperate on developing more expensive weapons systems, such as modern fighter aircraft.

But considerable overlap between two groups’ interests does not make those interests identical. American policymakers should always be aware of this distinction, especially during today’s current challenges.

The lead up to and domino effect of World War I is a prime example — smaller states allied to Great Powers with similar interests, eventually dragging those larger nations into wars that the larger states did not necessarily want or feel ready to fight.

Serbia appealed to Russia to intervene on its behalf in 1914 after Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum and then declared war following Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination by a Serbian nationalist. Though ill-prepared for a war (that would prove to be the downfall of its government), Russia’s close relationship with Serbia and ideological commitment to being a broader European protector of Slavic peoples pushed it into engaging–an ultimately fatal foreign policy mistake.

And on the other side of the conflict, Germany offered Austria-Hungary a “blank check” of its support for pursuing retribution against Serbia, which contributed to war breaking out and escalating once France honored its own alliance with Russia. Ultimately, Germany found itself routinely having to salvage the weaker Austria-Hungary from dire strategic situations at times when it needed its own troops elsewhere—all for a war that its ally’s actions helped drag it into initially.

By viewing allies’ interests as wholly aligned rather than recognizing where they overlapped and where they did not, European countries stumbled into a deadly conflagration all would have wished to avoid.

America hasn’t been immune from the challenge of distinguishing its own interests from its partners in more recent history either. While NATO was a necessary deterrent alliance during the Cold War, its purpose today is less clearly connected to vital U.S. interests, as are the goals of many of its members.

It’s crucial for lawmakers to appropriately balance engagement abroad to maximize the positive benefits of close ties while minimizing strategic liabilities that can result.

Alliances cost the U.S. in dollars and resources

While America’s leadership in NATO has helped keep Europe oriented toward U.S. foreign policy goals, it has also resulted in Europe underinvesting in its own security and becoming dependent on U.S. forces. American policymakers have complained about Europe’s “free-riding” off U.S. guarantees from early in the history of the alliance.

In a 1959 conversation with senior U.S. military leaders, President Eisenhower sought to prevent U.S. forces in Europe from taking on a permanent defense footing. He argued that Europe had time to recover from World War II and could now gradually take on a greater share of its defense burden while the U.S. reduced its own regional presence. The notes from that meeting reflect that Eisenhower’s critique is still relevant today:

The President said that for five years he has been urging the State Department to put the facts of life before the Europeans concerning reduction of our forces. Considering the European resources, and improvements in their economies, there is no reason that they cannot take on these burdens. Our forces were put there on a stop-gap emergency basis. The Europeans now attempt to consider this deployment as a permanent and definite commitment. We are carrying practically the whole weight of the strategic deterrent force, also conducting space activities, and atomic programs. We paid for most of the infrastructure and maintain large air and naval forces as well as six divisions. He thinks the Europeans are close to ‘making a sucker out of Uncle Sam’; so long as they could prove a need for emergency help, that was one thing. But that time has passed.

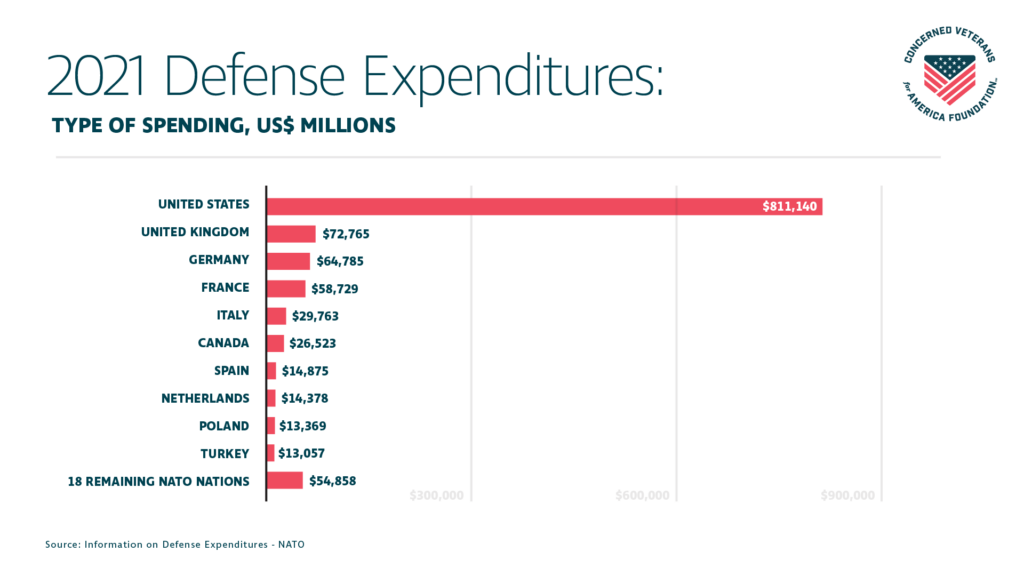

Unfortunately for the United States, its relationship with NATO-Europe has changed little when it comes to who bears defense burdens.

In 2022, only eight of 29 NATO powers outside of the United States—less than a third of the alliance—met the NATO-wide pledge to spend 2% of their GDP on defense. Of those European countries meeting their defense targets, Poland and the United Kingdom are the only two with large, well-equipped militaries likely capable of meaningfully altering the balance of power against a Russian attack. With an ongoing Russian invasion in its backyard, this trend of continued European complacency its startling.

And during the war in Ukraine, this disparity has been even more astounding.

The United States has pledged more aid to Ukraine than nearly the rest of the world combined as Europe’s own contributions lag, despite the war being in NATO-Europe’s immediate vicinity.

Americans have essentially subsidized the welfare states of wealthy European allies by paying for most of their defense, despite the European Union, which overlaps considerably with NATO, collectively having the world’s third-largest GDP.

America does benefit from having wealthy partners in Europe that share our interests, but neither the United States nor Europe benefit from the permanent expectation that America will always be the front-line of Europe’s defense. Instead, this status quo overstretches the U.S. military and encourages complacency among European allies. It also ignores the wisdom of Washington’s Farewell Address, which warns that “interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, [will] entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice.”

Informal alliances with the U.S.

The main focus of alliance conversations these days is NATO but diverging alliance interests don’t just occur in Europe. We have to consider the ramifications of informal security assurances, which differ from formal alliances, to partners we don’t have official defense treaties with as well.

The behavior of many U.S. security partners, such as the Gulf Monarchies of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, show the danger of being too closely associated with reckless actors. Though not permanent treaty allies, these partners cooperate closely with the U.S. in opposing Iranian influence across the Middle East and basing our forces to aid in this effort. During the war in Afghanistan and the height of the war in Iraq, these bases were more important for logistical reasons, but nowadays are increasingly less so as the U.S. attempts to shift focus to Asia.

Partners such as the Gulf States can create additional burdens for the United States in the region through overconfidence that they will have continued, unqualified U.S. support, regardless of their actions. At a certain point, ignoring the risks becomes irresponsible.

Despite their benefits for the U.S. elsewhere, Gulf partners have also backed Islamist rebel factions in Syria and Libya that have destabilized the region and contributed to refugee crises in Europe. They have prosecuted a bloody war in Yemen that drives one of the worst humanitarian disasters on record with U.S. munitions and logistical support. More recently, these countries have refused to increase oil production amid the war in Ukraine as the U.S. and Europe suffer higher prices. All these issues are part of the price of reliance on these nations.

Petro-states in particular tend to have structural issues with their foreign policy decision-making due to having many resources to spend abroad but typically low-quality governing institutions unable to do so wisely.

As a report from Defense Priorities outlines, the ambiguous status of these informal, or “quasi-allies” has several other drawbacks for American foreign policy.

The sense that certain countries are “allies” despite no formal treaty can confuse the public about what American obligations are abroad and create pressure for unwise interventions. These relationships can also promote an unrealistic idea that the U.S. backing down in any region endangers its credibility world-wide and can entangle us in open-ended conflicts with shifting end-goals, such as in Syria.

As in Europe, major non-NATO ally status can also make countries over-reliant on U.S. protection instead of investing adequately in their own capabilities. Taiwan is an example of this trend. It has largely dedicated a smaller percentage of GDP to defense spending since the late 1980’s and only trains its populace to resist invasion through a mere four months of required service despite souring cross-strait and U.S.-China relations.

These risks should inform debates over whether to extend new security guarantees to states in the Middle East or elsewhere.

Should the U.S. expand alliances – or should it shrink them?

While America should honor its treaties, the United States should be extremely careful about extending new security commitments to additional countries – and consider where it can re-evaluate the importance of risky commitments that already exist. The U.S. is already a formal ally to over 51 nations that it is treaty-bound to defend, mostly in Europe and the Americas. Additionally, the U.S. has 18 “major non-NATO allies,” including the Gulf Monarchies, who are able to more easily buy high-end U.S.-made weapons systems, enter training agreements with U.S. forces, or host U.S. troops or supplies on their territory.

Having this many security obligations at once already stretches American credibility, particularly for countries whose security challenges are minor at best to vital U.S. interests. It strains our resources and takes attention away from potential threats, such as China, that are much more apparent.

America should continue to value the positive relationships it has built with countries across the world. But in doing so, Americans should recognize that formal military treaties and informal security agreements are only one piece of how these relationships are built—U.S. economic, cultural, and technological dominance all help export U.S. values and influence abroad as much as, if not more than, formal alliance commitments and the risks those entail.

Though alliances can have value as a means of protecting U.S. interests, they are not ends in themselves. American policymakers should avoid allowing our existing alliances to subvert U.S. interests to other nations’ and remember the high risks of this taking place when considering new permanent security agreements.

Read about the past, present, and future of American alliances.